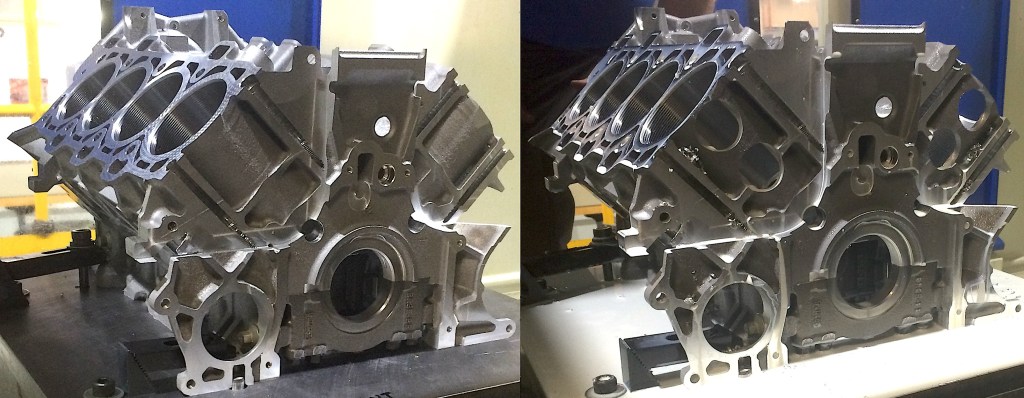

Welcome. This issue’s cover shows a V-8 engine block with part of the rear face milled away to expose the cylinders. Readers familiar with internal combustion engines have perhaps already noticed that there are two large holes drilled through each cylinder. This was a test part to develop a process for drilling large diameter breather holes all the way through an engine block, to increase air flow and provide more even flow through all cylinders. Since you need oxygen to burn gasoline, the more air you can force through an engine, the more gasoline you can burn per unit time, and the more horsepower you can generate. Breather holes were invented to exploit this observation, as were turbochargers, superchargers, and restrictor plates; fake cosmetic air scoops on car hoods also spring from this source, indirectly.

In this application there were two big holes per block, in the same locations as the smaller holes below the two test holes in each cylinder. The engine had thermally sprayed bore walls and the concern was that the coating would flake off during drilling. They also wanted to know what kind of drill to use and how long it would take. So I received a request to do some tests; the conversation went something like this:

Them: Dave, can you set up a machine with high pressure water-based coolant, buy some long, large diameter drills, and spend two weeks drilling big holes all the way through engine blocks?

Me: Hell yes.

This was a fun drilling job, even though it was a wet operation, meaning we pumped a lot of water-based coolant through the drill for lubrication and cooling. This is the standard way to machine in most automotive plants, but Ford usually used oil mist lubrication in new operations to reduce cost, because they’re only in it for the money. I disliked wet machining jobs at work for the same reason I dislike plumbing projects at home: because you always end up all wet and dirty, often with disturbing substances of unclear origin. It’s also hard to take a good video of a wet test, since the coolant splashes all over the camera; this is especially problematic if you want to use an action shot from the video for a poetry journal cover.

Pulsebeat is now in its fourth year and is cruising in overdrive, thanks to the many fine poets who contribute strong work, and to the readers who have spread the word in the absence of any marketing activity on my part. The reading period for Pulsebeat 11, which will be posted in May, begins February 1. Until May, enjoy the wonderful poems in this issue.